It's been nine months since my last blog post. Rumors and celebrations of my demise are premature; I have simply felt a profound reluctance to wade in the increasingly troubled waters of public media and the trendy nonsense that too often passes for professional wisdom these days. And in pandemic times, when most everything goes online, I feel a better place for me is in a stall to be mucked or sitting on a stump somewhere watching rabbits and talking to goats, dogs or ducks. Certainly they have a better appreciation of the importance of technology than most advocates of "artificial intelligence".

But for those more engaged with such matters, a recent blog post by my friend and memoQ founder Balázs Kis, The Human Factor in the Development of Translation Software, is worth reading. In his typically thoughtful way, he explores some of the contradictions and abuses of technology in language services and postulates that

... for the foreseeable future, there will be translation software that is built around human users of extraordinary knowledge. The task of such software is to make their work as efficient and enjoyable as possible. The way we say it, they should not simply trudge through, but thrive in their work, partially thanks to the technology they are using.

From the perspective of a software development organization, there are three ways to make this happen:

- Invent new functionality

- Interview power users and develop new functionality from them

- Go analytical and work from usage data and automate what can be automated; introduce shortcuts

I think there is a critical element missing from that bullet list. Some time ago, I heard about a tribe in Africa where the men typically carry one tool with them into the field: a large knife. Whatever problem they might encounter is to be solved with two things: their human brains and, optionally, that knife. In a sense, we can look at good software tools in a similar way, as that optional knife. Beyond the basic range of organizing functions that one can expect from most modern translation environment tools, the solution to a challenge is more often to be found in the way we use our human brains to consider the matter, not so much the actual tool we use. So, from a user perspective and from the perspective of a software development organization, thriving work more often depends not so much on features but on a flexible approach to problem solving based on an understanding of the characteristics of the material challenge and the possibilities, often not adequately discussed, of the available tools. But developing capacities to think frequently seems much harder than "teaching" what to think, which is probably why the former approach is seldom found in professional language service training, even when the trainers may earnestly believe this is what they are facilitating.

I'll offer a simple example from recent experience. In the past year, most of my efforts have been devoted to consulting and training for language technology applications, trying to deal with crappy CMS systems for which developers never gave proper consideration to translation workflows or developing methods to handle really weird outliers like comment translation for distributed PDFs or filtering the "protected" content of Microsoft Word documents with restricted editing to... uh... protect the "restricted" parts.

That editing function in Microsoft Word was new to me despite the fact that I have explored and used many functions of that tool since I was first introduced to it in 1986. I qualify as a power user because I am probably familiar with at least five percent of the program's features, though I am constantly learning new ways to apply that five percent. And the 95% remaining is full of surprises:

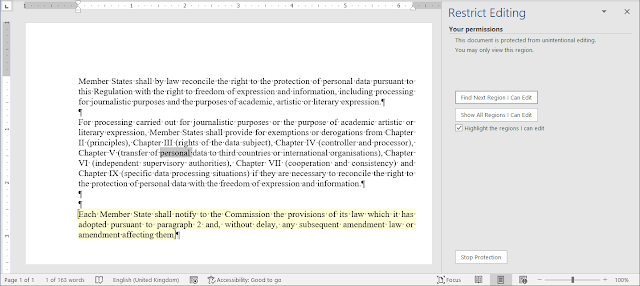

|

| Most of the text here can't be edited in MS Word, but default CAT tool filters cannot exclude it. |

Only the highlighted text can be edited in the word processor, and that was also the only text to be translated. The real files were much larger than this example, of course, and the text to be translated was interspersed with a lot of text to be left alone. What can you do?

It was interesting to see the various "solutions" offered, some of which involved begging or instructing the customer to do one thing or another, which is not always a practical option. And imagine the hassles of any kind of manual selection, copying and replacement if you have hundreds of pages like this. So some kind of automation is needed, really. Oh, and you can't even hide the protected text. It will import with the default filters of the translation tool, where it will then be indistinguishable from the actual text to be translated and it can be modified. In other words, bye-bye "protection".

What can be done?

There are a number of possibilities that fall short of developing a new option for import filters, which could take years given the often sluggish development cycles for any major CAT tool. One would be...

... to consider that a Microsoft Word DOCX file is really a ZIP archive with a bunch of stuff inside it. That stuff includes a file called document.xml, which contains the actual text of the MS Word document:

That XML file has an interesting structure. All the document text is in one line as one can see when it is opened in a code editor like Notepad++:

I've highlighted the interesting part, the part with the only text I want to see after importing the file for translation (i.e. the text for which editing is not restricted in MS Word). Ah yes, my strategy here is to deal with the XML text container for the DOCX file and ignore the rest. When the question was raised, I knew there must be such a file, but despite exploring the internal bits of MS Office files with ZIP archive tools for about a decade now, I never actually had occasion to poke around inside of document.xml, and I knew nothing of that file's structure. But simple logic told me there must be a marker there somewhere which would offer a solution.

As it turned out, the relevant markers are a set of tags denoting the beginning and end of a text block with editing permission. These can be seen at the start and finish of the text I highlighted in the screenshot. So all that remains is to filter that mess. A simple thing, really.

In memoQ, there is a "filter" which is not really a filter: the Regex Text Filter. It's actually a toolkit for building filters for text-based files, and XML files are really just text files with a lot of funky markup. I don't care about any of that markup except in the blocks I want to import, so I customized the filter settings accordingly:

A smattering of regular expressions went a long way here, and the expressions used are just some of many possible ways to parse the relevant blocks. Then I added the default XML filter after the custom regex text filter, because memoQ makes filter sequencing of many kinds very easy that way. This problem can be solved with any major CAT tool I think, but I don't have to think very hard about such things when I work with memoQ. The result can be sent from memoQ as an XLIFF file to any other tool if the actual translator has other preferences. Oh, the joys of interoperable excellence....

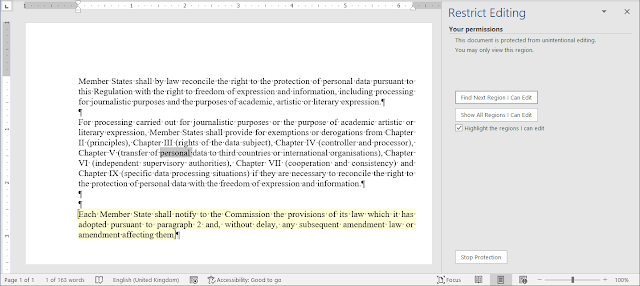

|

| The imported text for translation, with preview |

After translation,

document.xml is replaced in the DOCX file by the new version, and the work is done, the "impossible" accomplished without any new features added to the basic toolkit. Computer assistance is all very well, but without brain-assisted translation you're more likely to achieve half the result with double the effort or more.